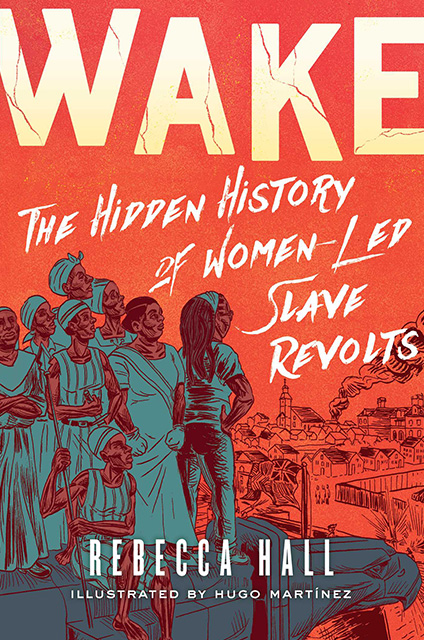

Dr. Rebecca Hall, illustrated by Hugo Martinez, lettered by Sarula Bao.

Simon & Schuster.

2021

“I am a historian, and I am haunted.”

These are the first words uttered by Dr. Rebecca Hall as drawn by illustrator Hugo Martinez in their new graphic novel Wake, The Hidden History of Women-led Slave Revolts. Martinez shows Dr. Hall staring out at the reader, a look of anguish on her face, capturing the emotional state one might feel waking from a disturbing dream. Her dream swirled around a slave-led revolt aboard The Unity and its passage from Africa to North America in 1770. In addition to the insurrection aboard The Unity, Dr. Hall introduces the reader to the journey she has been on—bringing to light the role women played in resisting enslavement through revolt. Her task is not easy as the people she is seeking are ghosts in time and are missing in the pages of history.

Dr. Hall is a Black lesbian, activist, and educator. A graduate of Swarthmore College, Hall has a law degree from Berkeley and worked as a tenant’s rights lawyer in California. She encountered racism in the justice system firsthand through the plaintiffs she represented and various personal microaggressions she endured, such as being mistaken for the defendant. In Wake, Hall is both a character and narrator. She tells the reader she “felt the need to see underneath the ‘justice system’—to get at the root of what was warping the world.”

In 2004 Hall decided to quit her job and pursue a Ph.D. in history with a minor in feminist studies from the University of California, Santa Cruz. As a student of gender and race in America, Hall quickly realized that to understand her experience as a Black woman today, she had to study chattel slavery. She decided to dive into the erased, unspoken blank spaces of historical documents to “read against the grain” and write her dissertation on women who led slave revolts.

Hall searched in New York City, London and Liverpool, England, digging in archives that looked like hoarders arranged them. Well-researched and digitized databases also were accessed. She sifted through the logs of captains of slave ships, old court records in both New York City and London, letters between colonial governors and representatives of the British Monarchy, newspapers clippings, and forensic examinations of bones of enslaved women uncovered in Manhattan.

Names were scarce. The slave revolt of 1712 in New York yielded four women: Sarah, Abigail, Lily, and Amba. All were executed. One of these was pregnant. Hall was not able to establish whether it was Sarah or Abigail, but the execution of the pregnant woman was stayed until she delivered because she was carrying was someone’s property. One of the leaders of a revolt in 1708 was referred to only as the Negro Fiend and was burned at the stake.

In the middle passage, the slaves who came on ships were branded, numbered, and referred to as cargo for insurance purposes. An insurrection of cargo was a revolt occurring on one in ten ships. Lloyds of London built a business insuring against the insurrection of cargo.

Wake is a visual presentation of Hall’s search process, driven by her desire to honour her grandmother, Harriet Thorpe, born into slavery in 1860. To see Hall’s journey in a graphic novel was an inspiration to me. Researching is absorbing and satisfying, but also lonely and frustrating, generating thoughts of giving up. The panels drawn by Martinez allowed me to “see” Dr. Hall’s journey and know that as an author-in-progress of historical nonfiction on a path fraught with similar obstacles, I am not alone.

Choosing to tell her story in graphic novel form was a challenge for Hall, an experienced academic writer who needed to learn the craft of writing for visual media. She liked the process. “The linear nature of text combined with the all-at-once of art allows for the reader to have a participatory experience.” For Hall, “having the past right up against the present was crucial.”

Close examination of Martinez’s drawings shows an array of complex images calling to the past to coexist with the present, all on the same page.

Hall’s decision to tell her story as a graphic novel was a challenge to me personally, uncovering an unconscious bias: comics are for kids. I have memories of reading comics in the garage of our house in Springfield, Ohio. Dad and my brother reading The Flash, Bat Man and Superman; me reading Wonder Woman; Mom inside with her copy of Fredric Wertham’s Seduction of the Innocent under her arm, sure that we three were going to hell. Hall’s book changed my perception of graphic novels.

Wake teems with information and perspective both on the history of racism and the ways racism still exists today. My criticism of the book is that she walked over the line of fact and fiction. She was transparent about this, informing the reader that she made educated guesses about the story implied by the facts, saying, “It is the least I can do for these women, using everything I know to be true about their lives and add the parts we don’t know but could be true.”

Hall researched tirelessly, evidenced by the long lists of primary source materials, secondary sources, and an extended bibliography available on her website. However, I am bothered about the blurring of the line between fact and possible fiction. Wake taught me that I need to be conscious of delineating and presenting my own story’s likely but not substantiated facts.

The book is too valuable not to recommend. It is appropriate for all levels of readers – from the older and cynical (me) to the young and wondering who might pick up a graphic novel, but NEVER touch a history book, and to those who do not read words, but can understand the past held on the page by the images.